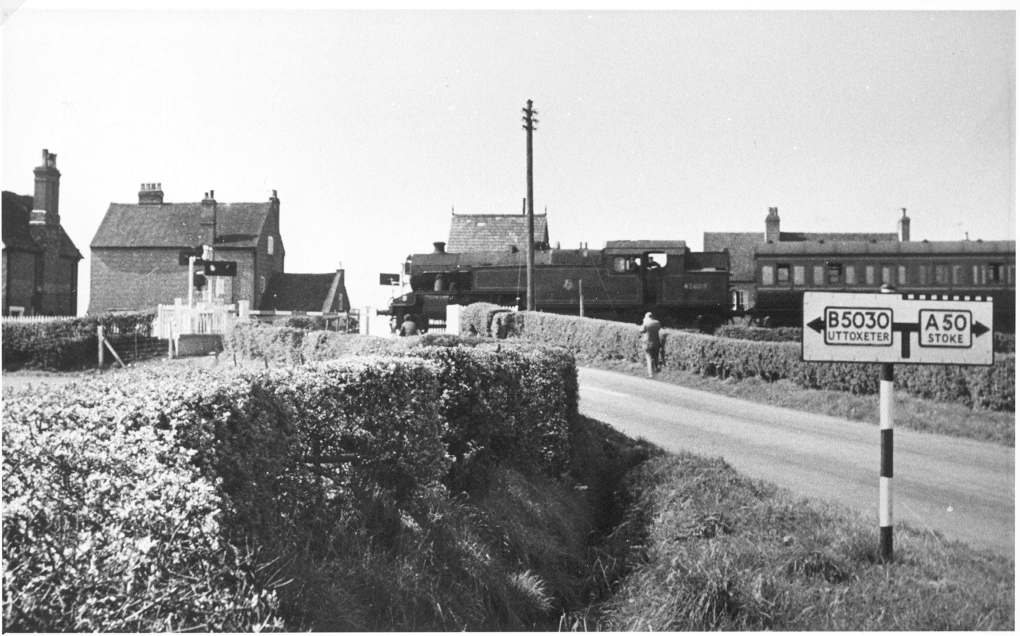

Plate 1: Spath Crossing in the Summer of 1961 whilst Attendance was still provided. BR Official / Nick Allsop Collection

DERBY AREA SIGNALLING

THE FIRST AUTOMATIC LEVEL CROSSING IN BRITAIN

The Behind the Scenes Story of its Development

Introduction

On Sunday 5th February 1961 the first automatic level crossing in Britain was brought into use. Whilst the technical nitty-gritty has been common knowledge for many years, it was only when the Ministry of Transport files at the Public Record Office (now of course the National Archives) were opened under the “Thirty Year Rule”, that we first learned how and why this insignificant crossing in rural Staffordshire came to make British railway history.

Plate 1: Spath Crossing in the Summer of 1961 whilst Attendance was still provided. BR Official / Nick Allsop Collection

Political Background

Since the earliest days of Railway Mania it was accepted practice that road users should give way to rail traffic where they crossed on the level. To state the obvious, a train cannot stop or manoeuvre as readily as a road user, no mater what form of transport that road user may be employing.

The safety arguments for road traffic yielding to trains are as strong today as they ever were in the 19th Century. The same cannot be said of the patience of the road user. The post war years have seen an inexorable rise in road traffic with a proportional decline in railway traffic. It is no surprise then that even by the 1950s the tide of public opinion was turning against the railway.

In an attempt to reduce the increasing delay to road traffic at railway level crossings, as early as 1954 the Ministry of Transport was tinkering with the long held traditions of the railway. As a counter to wandering animals (and people) it had been a requirement that the railway be securely fenced-in. Where there was a break in the fence to allow people to cross then there had to be a gate which was invariably fastened across the railway or the road but never left open to both.

The first attempt to lessen the delay to the road user was to dispense with the need to swing heavy wooden gates through 90º before and after the passage of a train. This was done by allowing the railway to install lifting barriers which would save the road user a few precious seconds. Of course the advantage to the railway was minimal. These barriers could only be used as a substitute for gates at manned crossing. There was no saving in what was becoming the most expensive resource — labour.

By this time, the railways and roads were both effectively controlled by the Ministry of Transport. In the case of the railway there was an additional strata of government in the form of the British Transport Commission, but ultimately, the Ministry ruled both roosts. All of which meant that both parties had a vested interest in automating level crossings; savings in time for the road user and savings in wages for the railway.

In 1956 a party of Civil Servants from the Ministry and Railwaymen set off on a fact finding tour of Europe to see what was going on over there and to explore if, and how, Continental practices could be applied to the British way of working. One member of the party was E.G.Brentnall OBE, the Chief Signal & Telecommunication Engineer for the London Midland Region.

This resulted in an Act of Parliament in 1957 which empowered the Minister of Transport to authorise “specially safety arrangements at public level crossings such as automatically or remotely operated barriers”. A series of “Provisional Requirements” were circulated to the railway by the Ministry of Transport on 1st May 1958.

It was no surprise to the Railway Inspectorate of the Ministry of Transport, therefore, when they received a letter from London Midland Region dated 15th April 1959 applying for permission to provide “an Automatically Operated Barrier Installation” at Spath in Staffordshire.

Curiously, the reason the LMR gave for seeking permission to automate this crossing was that “Spath signalbox and frame are due for renewal in 1959. The box is, however, no longer necessary as a block post, so that the only reason for renewing it would be to control the level crossing. It is considered the crossing is suitable for the provision of automatically-operated lifting half-barriers”. To suggest that the box was life-expired is a quite amazing statement especially when one contrasts the age and condition of Spath box with many of the other ex-North Stafford boxes in the area.

About Spath

As it stood in 1959, Spath was where the B5030 Uttoxeter to Ashbourne road crossed the Churnet Valley branch of the former North Staffordshire Railway. The line speed at Spath was a modest 45mph and there was a falling gradient of 1 in 396 in the Up direction. The LMR reported that there were 30 trains passing the box each week day.

The crossing was gated and was supervised by a small cabin of the NSR’s second design which stood on the Down side to the north of the road. The box was equipped with a 10 lever frame of which four were spare. The four interlocking gates were worked from a wheel in the box and the wickets were locked by the frame. The layout was, and always had been, plain line.

The following Sectional Appendix extract gives an idea as to the railway geography of the area:-

BRITISH RAILWAYS LONDON MIDLAND REGION SECTIONAL APPENDIX TO THE WORKING TIMETABLE AND BOOKS OF RULES AND REGULATIONS WESTERN LINES CREWE AND NORTH THEREOF

Page 130

UTTOXETER WEST AND EAST TO NORTH RODE JUNCTION

Uttoxeter

| (See page 127)

| (See page 127)

| Drivers must whistle when 1 mile distant from

| Seven Acres Level Crossing

| Drivers must whistle when 1 mile distant

| from Crakemarsh Level Crossing and

| Combridge Level Crossing.

Rocester

| See page 132 for Ashbourne line)

| (Level Crossing) 1636yds

Alton Towers

Oakamoor

|

|

Fig.1: BR(LMR) Sectional Appendix 1960 extract

Although not directly relevant to the story in hand, the operation of the intermediate Level Crossings mentioned in the Sectional Appendix is interesting, not least of which because they seem to have been totally ignored in the plans for Spath Crossing.

Seven Acres level crossing is referred to on the plans for Spath as “Cotton Mill level crossings” (note the plural). Warning bells were provided, manually operated from Spath and Uttoxeter North cabins. A warning notice was located on either side of each crossing; “When this bell is ringing trains are approaching this crossing”. The hand gates were kept padlocked.

At Crakemarsh crossing warning bells were operated by treadles. While the wickets were uncontrolled, the hand gates were operated by a resident female crossing keeper. Crossing keeper’s block indicators were provided.

The boxes on either side were much bigger affairs with Rocester having a 36 lever frame and Uttoxeter North Junction, which controlled one corner of a triangular junction, had 29 levers including nine spares. It was to be Uttoxeter North which would take over supervision of Spath barriers.

Turning to the road layout at Spath, this wasn’t as simple as I suspect the Ministry would have hoped for in a pioneering installation. The Uttoxeter bound approach was reasonably straight with 250 yards of view. On the other side, however, there was a busy ‘T’ junction a mere 100 yards from the crossing with buildings on the corner. This was aggravated the railway and the road crossing one another at a slight skew and by the crossing itself forming something of a hump, restricting views across the railway.

Fig. 2: Diagram of Spath Crossing prior to Modernisation

This ‘T’ junction was to prove problematical later on, but in the early days the Ministry didn't seem at all concerned that they were exceeding the limits on traffic volume they had themselves dictated in early guidelines for automating crossings.

Plate 2: Spath Signal Box after modernisation looking in the Down direction towards Rocester.Nick Allsop Collection.

The LMR had carried out two traffic surveys;

| 10th – 16th August 1958 (7 days) Summarised, the average daily user is as follows:- | |

| Motor vehicles | 1,517 |

| Motor cycles | 161 |

| Bicycles | 157 |

| Pedestrians | 62 |

| Animals | 7 |

| Horse drawn vehicles | (total of 3 in the week) |

| Trains | 26 |

| Note; the above figures do not include road traffic which passed during the 18 hours 40 minutes when the signalbox was closed at the weekend | |

| 6th – 11th October 1958 (6 days) Summarised, the average daily user is as follows:- | |

| Motor vehicles | 1,300 |

| Motor cycles | 138 |

| Bicycles | 163 |

| Pedestrians | 40 |

| Unaccompanied children | 12 |

| Flocks of sheep | 2 in the week |

| Herds of cattle | 1 in the week |

| Horse riders | 4 in the week |

| Horses | 2 in the week |

| Horse drawn vehicles | 1 |

| Trains | 34 |

Fig. 3: Traffic Censuses carried out at Spath

There was a footnote to the survey pointing out that “in the Summer, particularly at holiday times, road traffic is sometimes heavier than usual because of visitors to Alton Towers”.

It is clear that, come what may, this request from the LMR was going to get approval. An internal minute dated 8th May 1959, in response to the letter from the LMR reads; “This appears to be an excellent crossing for an experiment with automatic half barriers. The number of motor vehicles is slightly higher than we had in mind for the first experimental equipment but we feel that this is more than compensated for by the fact that there are few trains and that the speed of trains is slow. visibility is also good". This trade-off between road traffic and rail traffic was to become enshrined in the criteria for all future installations.

The Installation

What was proposed for Spath was what we today refer to as “Automatic Half Barriers”. The barriers and control equipment at Spath were manufactured by the Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company Ltd to a design produced by the British Transport Commission and based upon the “Provisional Requirements” of 1958.

As they are so prevalent today, it is somewhat unnecessary to describe what an "Automatic Half Barrier" level crossing looks like or what equipment was installed. Most will be aware that the single steady amber indication to road traffic was not present in the original installations, otherwise, apart from a curiously old fashioned look, the crossing at Spath was equipped in a manner very similar to today’s crossings.

The pioneer crossing was equipped with a “Another Train Coming” notice which was not universally fitted to subsequent crossings. Whereas the modern standard is to place this illuminating sign under the primary Stop road signals, the original had them on the far side of the crossing under ‘secondary’ Stop signals — which were themselves dispensed with in subsequent installations.

Lowering of the barriers was caused by occupation of Track Circuit “T.4” (up line) or “T.2” (down line) after delay of eight seconds. Raising of barriers was invoked by occupation and clearance of Track Circuit “T.4” and Treadle “Q4” being operated (up line) or “T.3” and Treadle “Q3” (down line) unless a second train intervened. The barriers were maintained down and “Second Train Coming” indicators illuminated by occupation of Track Circuit “T.5” (up line) or “T.1” (down line) when a second train intervened. The position of barriers was indicated in Uttoxeter North signal box as was the state of the power supply.

Fig. 4: Spath after Modernisation

The position of the “Point of Operation” and "Strike In Point" was, course, dictated by the maximum line speed so as to ensure a minimum of five seconds would elapse between the barriers reaching the lowered position and the fastest train passing. In the original specification produced by the London Midland Region, these distances were worked out based on an assumed line speed of 60mph (it was thought “advisable” to do so). On that basis, the Point of Operation was set at 616yds and the Strike In Point at 909yds.

By 1st July 1960, it had no longer been thought so advisable to cater for 60mph running so the distances were revised to 472yds and 652yds respectively, as required for 45mph. These distances were to be again revised, this time for 55mph, only a few months after the crossing was brought into use. This was because the railway pointed out that steam hauled express freights used the line and they were not necessarily equipped with a speedometer.

Meanwhile, there was a considerable amount of debate going on within the Ministry of Transport, this time with its own road engineers. As this was a completely new phenomenon as far as road traffic was concerned, there was intense discussion concerning the road sign requirements. Of course the proximity to a ‘T’ junction exacerbated this and the internal (and external) arguments rumbled on long after the crossing was brought into use.

The Crossing Opens

Work to install the equipment commenced in late November 1960. Authority for the crossing was granted by "The British Transport Commission (Churnet Valley Line) (Spath Crossing) Order 1960" which came into force on 19th December 1960.

By Thursday 2nd February 1961 work had progress sufficiently to allow Col. McMullen of the Railway Inspectorate to formally inspect the crossing. A locomotive and saloon was provided for the occasion. All must have proceeded smoothly and to the Inspector’s satisfaction with the operation of the equipment as he granted permission for the crossing to be taken into use the following on the Sunday, “subject to completion of the fencing and the road surface as well as attendance at the crossing until further notice”.

Fig. 5: The Publicity Pamphlet

As the education of road users was seen as the key to the safety of the system, British Railways embarked on a huge publicity campaign. Leaflets were printed and circulated to all local residents, schools were visited and much use was made of the media — a pattern followed with most new installations ever since.

A press conference was held at the crossing during the morning of Monday 6th February. A special train formed of a two car DMU was arranged to shuttle back and forth between Uttoxeter and Rocester thereby operating the crossing at a variety of speeds. There was a good turn-out of Gentlemen of the Press and stories appeared in all the national papers as well as the Birmingham Post, the Yorkshire Post and the Liverpool Daily Post.

This snippet from the Daily Mail on 30th January is typical of the press coverage (although it predates the actual opening); “ROBOT CROSSING - Britain's first train controlled level crossing was tested yesterday at Spath, Staffordshire. Instead of gates it has red and white poles which are automatically lowered across the road when a train trips and electric contact on the line”

The Financial Times, as befits its market, concentrated on the economics (and thereby provides the only mention I have found of the cost). The FT told its readers that “the Installation has cost between £5,000 and £6,000 but it is estimated that after three years there will be a net saving of about £2,000 a year represented in the wages of the three signalmen who formerly looked after the gates and in maintenance”.

The Early Days

Once the hoopla of the press launch had died down the crossing was left to its own operation. As required by the Railway Inspectorate — and as became normal practice ever since — a temporary crossing keeper was left “in attendance” at the crossing. His function was to see that the equipment operated correctly and, as far as was in his power, that the public used the crossing correctly.

As Spath was no longer a Block Post and all the signals had been taken away, the crossing keepers had little influence over railway operations. They were encouraged to look out for motorists disregarding the red Stop signals at the crossing. On 27th April 1961 a Walter John Cope (38) of Balance Hill, Uttoxeter did just that. On 6th July he pleaded guilty before Uttoxeter Magistrates and was fined £8. The court heard that he had crossed against the red light and just cleared the descending pole as the train was only 150 yards away. The Magistrate launched into a passionate speech about endangering the lives of all concerned, and how it was a serious offence which deserved serious punishment — all of which was reported widely in the press, to the railway’s evident delight.

Plate 3: Spath Crossing with an Up Passenger train. Nick Allsop Collection

Not that relations with the local judiciary remained rosy. After the eighth motorist appeared before the bench, the Clerk to the Court felt compelled to write to the railway, who passed the correspondence on to the Ministry. There was, it seemed, a widespread feeling that the signing was inadequate and the lights were too dim.

This reopened the debate on alternative signing. Matters were not helped by the fact that the Staffordshire County Council were the relevant Highways Authority. They clearly had their own ideas about how the level crossing should be signed and in July 1961 proceeded to take down the signs prescribed in the Order made by the Minister of Transport and replaced them with their own. The Prescribed signs read “Train Operated Signals and Barriers Ahead”. Staffs C.C. thought these signs too wordy and difficult for motorists to take in. Their idea was to replace the signs with the then standard sign for traffic lights — thereby confusing the issue even more as the crossing lights looked nothing like the red/amber/green signals depicted. Needless to say Whitehall took a very dim view of this and the council were instructed to replace the correct signs forthwith!

Further criticism from Staffordshire County Council provoked a stinging response from W.F.Adams of the Ministry’s Traffic Engineering Branch. Mr. Adams believed that any problems were due to wilful disobedience by motorists rather than an inability to stop. He rejected out of hand a request for amber lights to be positioned in advance of the crossing. He did concede that the Ministry might consider amber lights if sighting problems required them but contended that was not the case at Spath. Similarly, a request that the Stop signals be repositioned or realigned vertically was dismissed as they would no longer be a “lawful traffic sign”.

The suggestion that the Red signals were too dim was considered to have some merit. It was revealed that whilst the lights complied with the relevant British Standard for traffic lights, it was stated that “our established traffic signal firms give us signals which are substantially better than BS505”. The internal memo suggested that “an unofficial word with the railway” might resolve this with a view to them using better lenses!

The Crossing Becomes Established

By July 1961, the railway was becoming anxious to withdraw attendance at the crossing as all was working well. Indeed the Ministry was close to granting permission when word reached them of a problem. As had been pointed out by London Midland Region in the original application, there were seasonal peaks at the crossing due to the proximity of Alton Towers. With ‘T’ junction a mere 100yards beyond, traffic tailing back over the crossing was inevitable — even in 1961. One has to feel sorry for the crossing keeper. As he would be unable to (officially) direct road traffic he would be forced to sit idly by and there would be nothing he would be able to do to prevent a potential tragedy.

The Ministry weren”t happy at this situation and required the railway to maintain attendance and report as to how many occasions this problem was arising. Of course, as the only person who was there to record when this was happening was a railway employee, it is no surprise that in September LMR reported there had been no further occurrences and that they couldn’t understand why anyone had thought there was a problem in the first place! Consequently, on 26th September 1961 Col W.P.Reed OBE of the Railway Inspectorate consented to attendance being withdrawn, conditional on signs being erected which read “Do Not Stop On The Crossing”.

In his original inspection Col McMullen had recommended that the operation of the crossing should be observed by a crossing keeper during periods of high wind or snow as he had doubts as to the equipment’s ability to work during those conditions. Thus the LMR provided attendance during the winter of 1961/62. They later applied for, and received, formal permission to dispense with this requirement.

This crossing never attracted the safety paranoia attendant at many subsequent installations. A particular example of which was the sit-ins and deputations to see Ernest Marples (the then Minister of Transport) which the half-barriers at Egginton Goods, near Derby, attracted. The Staffordshire Advertiser did print an editorial expressing some disquiet but this was simply resolved by soothing words to the Editor from the Ministry.

All the local residents had cause to complain about was the additional whistling from the trains, brought about by the two "Whistle" boards on either side of the crossing. The railway was sympathetic and the LMR’s General Manager wrote to the MoT to “suggest that one long whistle when the train is passing the whistle board should suffice and ask if approval could be given to this as a special case”. The Ministry weren’t so understanding simply replying that “I feel we cannot withdraw the instruction to whistle, but the need may have been so emphasised to engine drivers that they may have overdone it”.

The saga of the road signs continued into the Summer of 1962. Alterations had been made to the signs and British Railways wrote to the Ministry asking if it would persuade Staffordshire County Council to pick up the £139 bill!

After all that, the Ministry’s file on the crossing is marked thus; “26th May 1965; Leek - Uttoxeter (Churnet Valley) line closed. Track to be disposed of shortly. Spath Level Crossing now out of use”. There may have been only just over four years worth of use of the crossing but the lessons that were learned in the implementation of it were applied to dozens of subsequent installations.

Until, that is, 6th January 1968 when a Scamell tractor drew a huge abnormal load toward an Automatic Half Barrier crossing at Hixon, coincidentally also in Staffordshire. From that day on, most of the lessons had to be learned all over again.

Sources:

Thanks to Nick Allsop for providing the illustrations.

Dave Harris, Willington, Derby, UK.

Email: dave@derby-signalling.org.uk

Page last updated: Tuesday, 25 August 2015